Notes can record audio and provide transcriptions, starting with iOS and iPadOS 18.

The Notes app in iOS 18 and iPadOS 18 makes it easy to add an audio recording to a note, and create a written transcription of it if desired. Here's how to do it.

It has long been possible to add an audio recording to a note created in the Notes app, but in earlier iOS versions it was a little more cumbersome. Users would open the Voice Memos app, record the audio, and then attach that recording to a new note in the Notes app.

As of iOS 18, that functionality is directly available in Notes — though it is still somewhat hidden until you know how to find it. The big change compared to the previous Voice Memos app is that Notes can now also provide a written transcript of what was said, if you are using an iPhone 12 or later.

It is important to note that the audio transcription feature is available only for various versions of English. This includes US and UK versions, along with Australian, Irish, New Zealand, and South African.

This new feature will be a godsend to students, board members, employees, and the secretaries of organizations everywhere.

Being able to quickly and easily reference a written version of what was said in a meeting or classroom will help users retain the information better. They will also be able to summarize key points, and separate action items from other information.

Having the original audio to review is also useful. As with audiobooks, re-listening to a speech or lecture can add the speaker's tone, passion, and context to their words, making it come alive in a way that a straight transcript cannot.

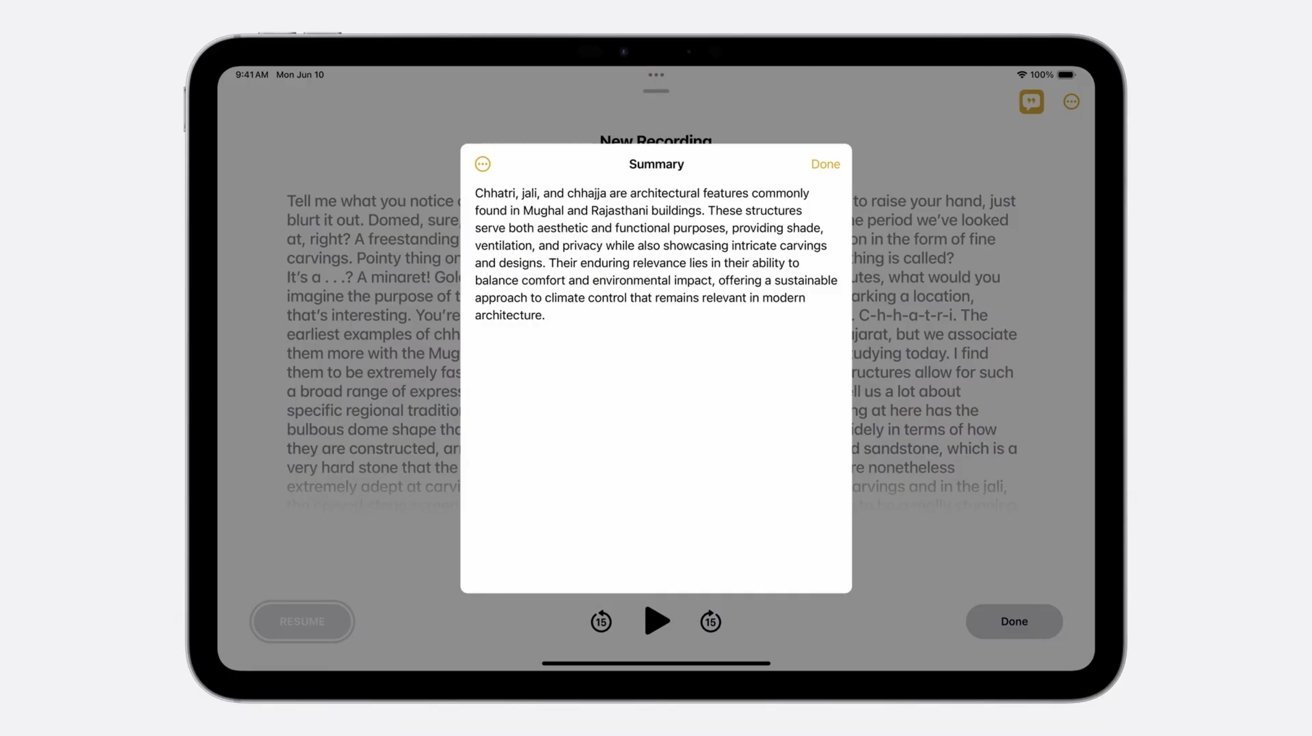

While not always 100 percent accurate, the transcript feature will make your notes more valuable to you, and more shareable with others. On devices capable of running Apple Intelligence, the summarizing feature within it can create the summary itself if the user desires.

Recording inside the Notes app

When you first open a new note in Notes, you'll see a plus button on the lower right side of the note, just above the on-screen keyboard. Tapping it will pop up a set of tools to use in your note.

These include font controls, bullet lists, table tools, an attachment button, drawing tools and, if available, an Apple Intelligence button.

- Tap on the attachment button.

- A menu of options comes up, including "Record Audio."

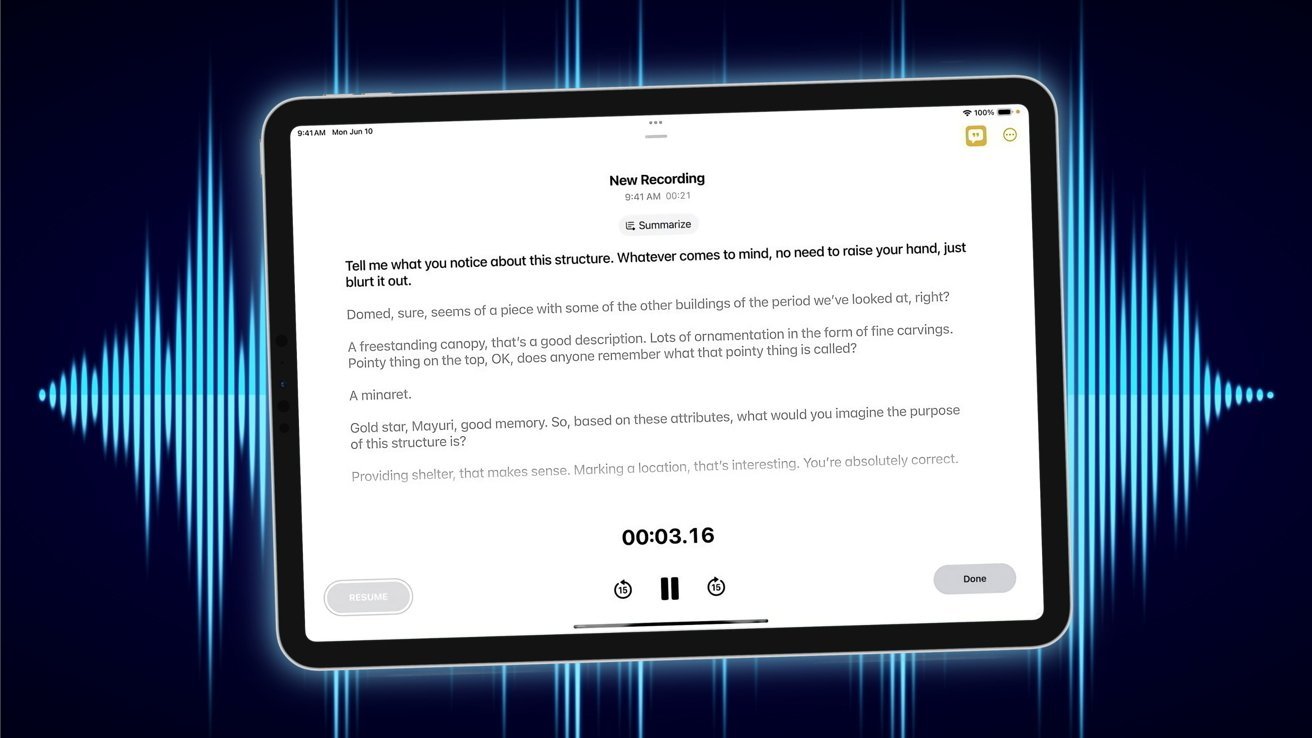

- Tapping that will cause a "New Recording" screen to appear, just as it does in the Voice Memos app — which is still available as a separate app.

- To start a recording, press the red button at the bottom of the screen, and check that the iPhone's mic is picking up your voice.

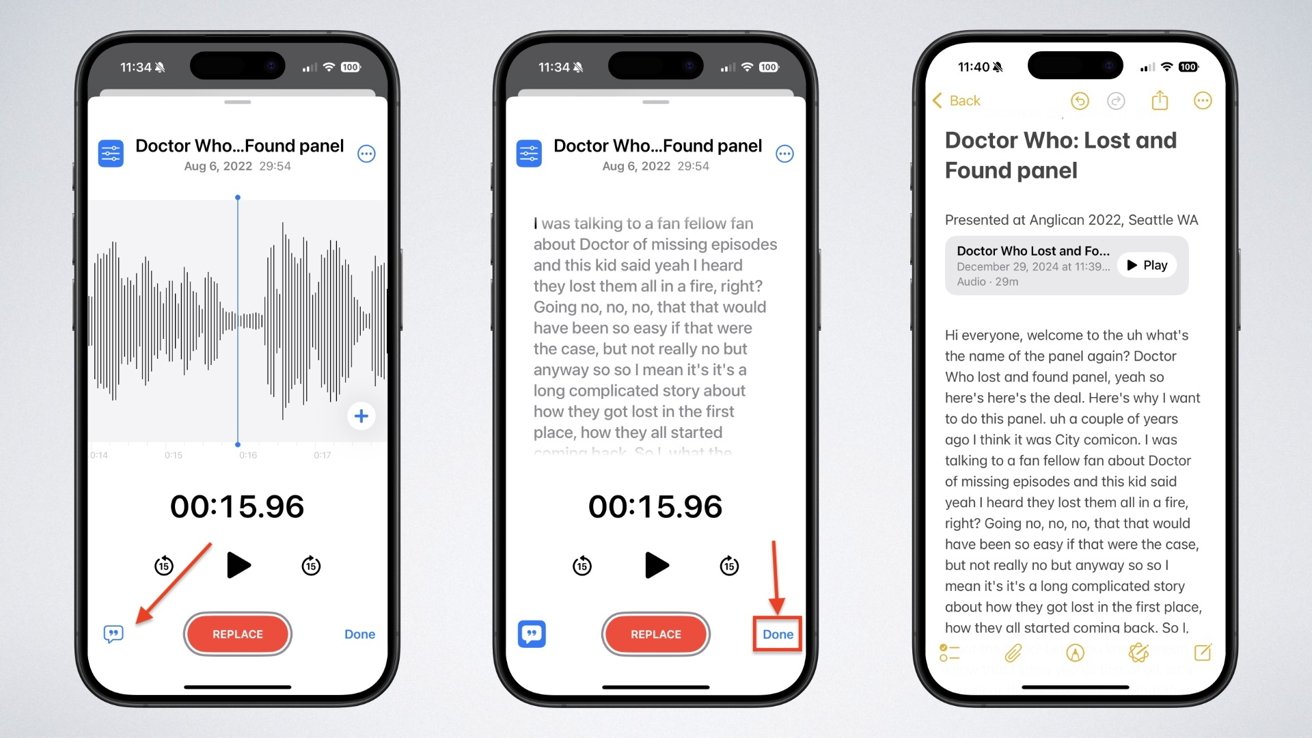

Three iPhone screens show audio editing with waveforms, playback controls, and a transcript. The last screen displays a saved note with text from the audio.

Three iPhone screens show audio editing with waveforms, playback controls, and a transcript. The last screen displays a saved note with text from the audio.

You can pause the recording to collect your thoughts and then resume, or just record an entire meeting, lecture, or panel directly.

- Press the record button again to stop the recording.

- To the left of the record button is a "word bubble" button with quote marks in it.

- Tapping that button will provide a real-time transcript of the audio.

Adding and viewing the transcript, and more

You can also wait until the recording is done, and tap the Done button to the right of the record button to generate a transcript. The full transcript will then appear in a new window, with an audio block in gray and the first couple of lines of the transcript along with a "play" button.

To add the recording to your note:

- Look for the "three dots" icon at the top right, and tap it.

- Tap "Add Transcript to Note."

- You can then edit the transcript to correct any errors.

You also have another option in that same menu to copy the transcript, which allows you to paste it directly into another program — such as a word processing app, a blog post, or other options.

You can also record and transcribe audio on any iPad model that supports iPadOS 18 or later. Audio transcription from the Notes app is also available on any Mac with an M1 processor or later, and running macOS Sequoia or later.

If it is available on your Mac, you can also use Apple Intelligence tools to summarize the transcript, proofread it, or rewrite portions in a different style.

With Apple Intelligence, you can summarize a transcription directly in Notes.

With Apple Intelligence, you can summarize a transcription directly in Notes.

Apple Intelligence is currently available on the iPhone 15 Pro or Pro Max, or the iPhone 16 models. It's also available on iPads using the A17 Pro or M1 or later chips running iOS 18 or later, and Macs running macOS Sequoia 15.1 or later, and using an M1 chip or better.